Mar-a-Lago: Where Everyday is a Holiday

Amanda Walters

Vertigo at Mar-a-Lago.

Settled on the eastern coast of South Florida, there is a prominent, and now famous estate. Its massive and well-manicured lawn is dotted with an innumerable variety of palm trees with various heights, shapes, and shades of green. Its structure contains the typical hues of the area, beige stucco with red tile roof, but its aesthetic likeness to the abutting estates ends there. Nearby neighbors dwell in rectangular boxes, with façades culled from their favorite vacation destinations: the row of arches like the ones they saw on their trip to Venice, or the gabled roof and balconies of the Swiss chalet where they stayed in the Alpines. The sprawl of this estate is different; it is made up of a confusion of small and big structures, attached to one another like barnacles or reaching tendrils. A high tower juts out from the already bewildering variety of hipped and gabled roof tops, and every third roof contains a steeple. The shape of the substructures is constantly varied; some of the segments of structures are round, some rectangular. The thought of navigating this disorientation of sub-structures overwhelms.

The estate was built in the 1920s, the beginning of the depression in Florida, by its proprietor and processed-cereal corporation heir, Marjorie Merriweather Post, and the architect Marion Sims Wyeth. Post weighed-in heavily on its design, by her request it was to combine the Spanish revival style already so popular in the region, with Venetian, and Portuguese styles, all set in a sub-tropical setting.

The estate was built in the 1920s, the beginning of the depression in Florida, by its proprietor and processed-cereal corporation heir, Marjorie Merriweather Post, and the architect Marion Sims Wyeth. Post weighed-in heavily on its design, by her request it was to combine the Spanish revival style already so popular in the region, with Venetian, and Portuguese styles, all set in a sub-tropical setting.

Ultimately, the estate would best be described as Hispano Moresque. Adding to the global identity crisis of the estate, many of the 58 rooms have their own unique, and often place-based theme: a Dutch room is located across the hall from the Portuguese room, a Norwegian room in the owner’s suite, and a neo-classical Adamesque room next to the Spanish and Venetian rooms. They named the estate Mar-a-Lago. To preserve the prestigious legacy of the estate she toiled to construct, Post willed Mar-a-Lago to the National Parks Services to be used as a Winter White House after her death in 1973. Deemed far too expensive to keep up, and after many years of complete nonuse, the estate was given back to the Post Foundation in 1981 and put on the market soon after. Donald Trump purchased the estate from the Post Foundation in 1985, ran for president thirty plus years later, won, and thus, Mar-a-Lago became the Winter White House.

The prophetic condition of the estate has made many a less and less interesting headline, but this prophecy or coincidence only begins to unravel the cozy relationship between the estate, its national leader inhabitant, and its first inhabitant, Marjorie Merriweather Post. Our two hosts look quite different. Post was known for her philanthropic nature, the estate was given-over time and time again to serve the needs of others. At one point it was used as an occupational therapy center for wounded World War Two veterans. For many years the estate hosted Red Cross fundraising events. Barnum and Bailey once performed on the lawn to underprivileged children. While the biographies of our two hosts may read strikingly different, the latter inhabitant is a transparent representation of the ideology that pervaded the site from its creation. Trump’s display of luxury and leisure mixed with capital power is mirrored throughout Mar-a-Lago, a landscape built of the same ideological material. His additions to the estate offer a view to the subtle shifts in the aesthetic of capital over the last ninety years. To the leisure class aesthetic that sustained through Post’s rein, Trump adds the element of leisure-worker. With the addition of work to the leisure class, the production of capital is demystified. In Post’s day it was distasteful to consider the money used to pay for the shiny objects. At Mar-a-Lago today the production of capital is transparently valorized as a form of power. The private estate was transformed into a revenue prospect as a private club, where members can play golf, swim in the pool, or eat in the dining room. Since becoming the most important worker in the United States almost a year and a half ago, Trump has spent about fifteen percent of that presidency at the South Florida vacation estate.1

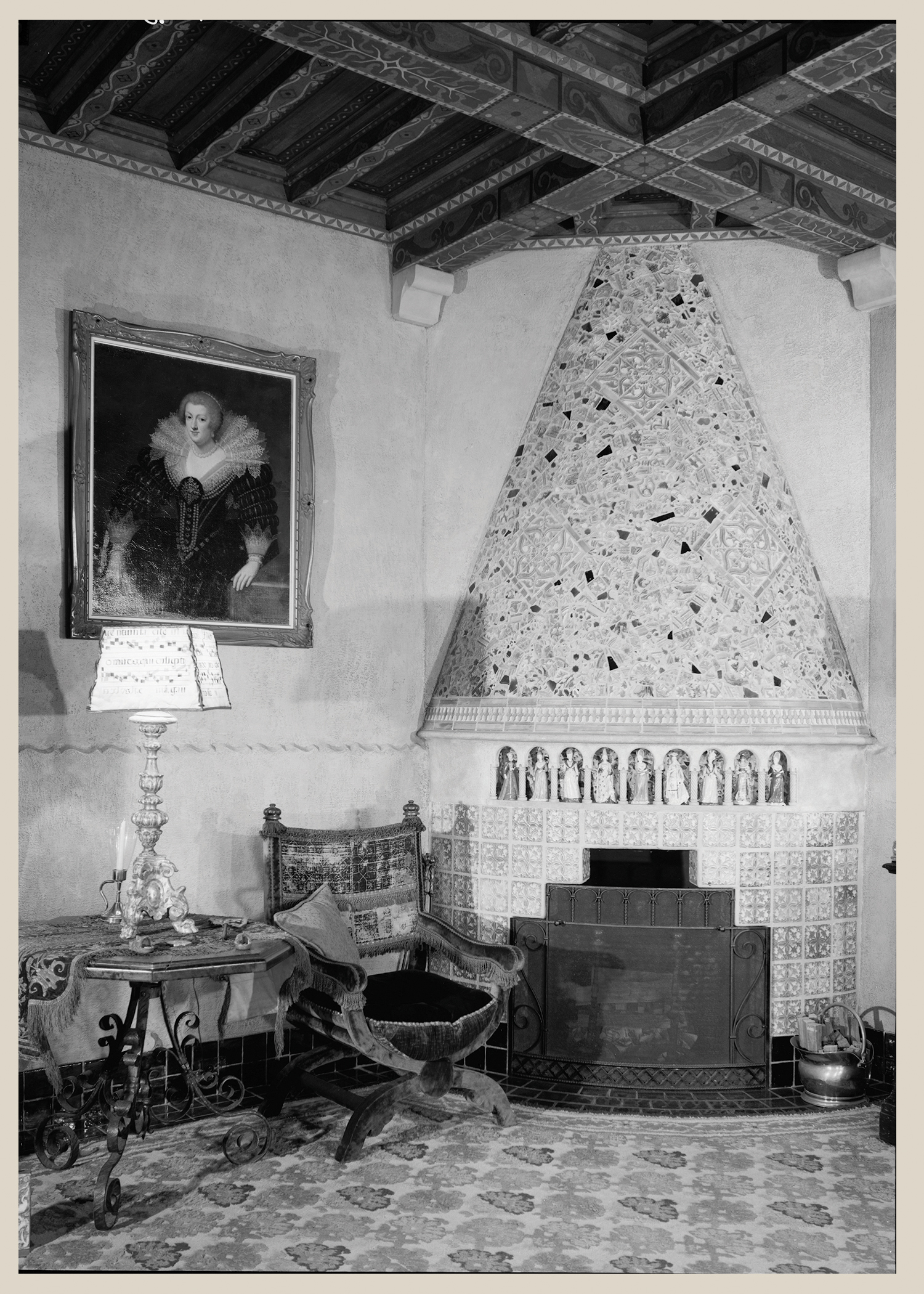

Library of Congress, April 1967, Hooded fireplace in

Spanish Room, Photos from historical survey, HABS FL-195.

Spanish Room, Photos from historical survey, HABS FL-195.

Library of Congress, April 1967, Dutch Room from south, showing delft tile decoration on fireplace and sconces, Photos from survey, HABS FL-195.

Library of Congress, April 1967 Patio looking south showing pattern of hexagonal

Moroccan tile pattern. Photos from survey, HABS FL-195.

Post perfected the earlier form of this aesthetic. She was a sign of elitism at the time of Mar-a-Lago’s construction, and a walking advertisement for the leisure class. The first quarter of the twentieth century experienced an economic boom that resulted in a proliferation of the elite class ideal. Post’s eccentricity was accepted as the outlandishness of wealth, a necessary asset to distinguish her as an elite in the leisure class. Her parties were featured in magazines and newspapers that celebrated her style, her menu, and the general exuberance of her outward facing life and home.

The estate itself is an unintentional museum to this aesthetic. Cultural objects and patterns are organized into discrete sections, removed from the rituals and practices of their makers, collected by Post or imported on her behalf, and organized to create a new cultural experience. This experience neuters all the potential resonance of the object– leaving only the aesthetic of capitalism. Mar-a-Lago is a living museum to that aesthetic. This museum provides a very particular and niche experience, but one that touches all other narratives. From this singular location, we can observe how the aesthetic of late stage capital was born and then perfected. At its creation, this site served to aestheticize the colonial culture collection. Objects, patterns, plant-life collected from regions all over the globe were combined to create an aesthetic experience. No longer were the purposes of these objects to inform the viewer of rituals in another land as they are exhibited in the colonial museums of the past. Knowledge is not the power of this economy. These objects are no longer artifacts, but vessels of experience for the leisure culture.

The estate itself is an unintentional museum to this aesthetic. Cultural objects and patterns are organized into discrete sections, removed from the rituals and practices of their makers, collected by Post or imported on her behalf, and organized to create a new cultural experience. This experience neuters all the potential resonance of the object– leaving only the aesthetic of capitalism. Mar-a-Lago is a living museum to that aesthetic. This museum provides a very particular and niche experience, but one that touches all other narratives. From this singular location, we can observe how the aesthetic of late stage capital was born and then perfected. At its creation, this site served to aestheticize the colonial culture collection. Objects, patterns, plant-life collected from regions all over the globe were combined to create an aesthetic experience. No longer were the purposes of these objects to inform the viewer of rituals in another land as they are exhibited in the colonial museums of the past. Knowledge is not the power of this economy. These objects are no longer artifacts, but vessels of experience for the leisure culture.

The curation of those cultural objects, removed from their culture and history, creates a monocultural otherness. This aesthetic foregrounds the viewer’s experience over the ritual or labor history of its maker. The thrill of unknown places is sanitized and prepared for a safe experience. It hybridizes all the cultures the objects were culled from into a singular, clean and tidy entity. Tropical palms line the courtyard floor, a glazed Spanish tile set in a Moroccan pattern. Copies of art works mingle with original works without any notation of their difference: tapestries taken from a palace in Venice are shown against copies of frescoes by Benozzo Gozzoli and Riccardo-Medici Plazzo, found in Florence, framed by a room otherwise covered entirely in gold leaf.

The man responsible for realizing the grandeur of the gold leaf room was interior designer Joseph Urban. At the time he was contracted by Post to design the estate’s interior, Urban was best known for his scenic set design and architecture for theaters. His experience in taking an audience to a world far, far away was fully utilized at Mar-a-Lago. In a collaboration with Post, Mar-a-Lago would become a living museum to Post’s travels, filled with objects she collected.2 Each room represents a different destination by theme, but not necessarily historical accuracy.

The man responsible for realizing the grandeur of the gold leaf room was interior designer Joseph Urban. At the time he was contracted by Post to design the estate’s interior, Urban was best known for his scenic set design and architecture for theaters. His experience in taking an audience to a world far, far away was fully utilized at Mar-a-Lago. In a collaboration with Post, Mar-a-Lago would become a living museum to Post’s travels, filled with objects she collected.2 Each room represents a different destination by theme, but not necessarily historical accuracy.

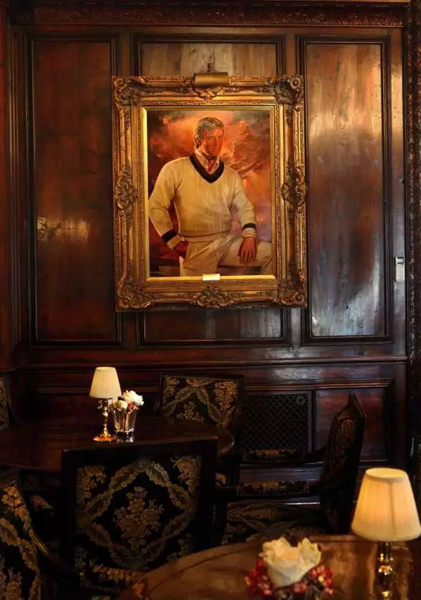

Ralph Wolfe Cowan, The Visionary, 1989.

Photo from Palm Beach Post.

The man responsible for realizing the grandeur of the gold leaf room was interior designer Joseph Urban. At the time he was contracted by Post to design the estate’s interior, Urban was best known for his scenic set design and architecture for theaters. His experience in taking an audience to a world far, far away was fully utilized at Mar-a-Lago. In a collaboration with Post, Mar-a-Lago would become a living museum to Post’s travels, filled with objects she collected.2 Each room represents a different destination by theme, but not necessarily historical accuracy.

Through time, the museum has changed slightly to incorporate the formal qualities of its new host. This style is dominated by massive portraits of Trump in looming positions that denote power, similar to portraits of the old imperial leaders, only these portraits include symbols of leisure, as work and leisure are confused and hybridized. One such example is found in the Mar-a-Lago club dining room, mounted on a wallsuch example is found in the Mar-a-Lago club dining room, mounted on a wall of darkly colored ornate tropical wood. The painting portrays the man in white tennis clothes, fresh off the court, posed in front of a cloudy sky with a singular beam of light streaming down onto his left shoulder. The beam whispers ‘chosen one.’ Another example is found in a popular marketing photo for the estate, now established as a private club and resort, Trump stands in a room covered almost entirely in gold leaf. For the portrait Trump chose an ensemble of golf attire, supported by a prop in the form of a golf club.The photo is shot fromjust above the ground as to give the proprietor a looming quality. He is surrounded by dark wood tables with gold trim and a pearlescent and ornately patterned living room set. In the center of the image, and just over his right shoulder, hangs a massive and elaborate chandelier. Each element of the room suggests pomp and splendor.

Through time, the museum has changed slightly to incorporate the formal qualities of its new host. This style is dominated by massive portraits of Trump in looming positions that denote power, similar to portraits of the old imperial leaders, only these portraits include symbols of leisure, as work and leisure are confused and hybridized. One such example is found in the Mar-a-Lago club dining room, mounted on a wallsuch example is found in the Mar-a-Lago club dining room, mounted on a wall of darkly colored ornate tropical wood. The painting portrays the man in white tennis clothes, fresh off the court, posed in front of a cloudy sky with a singular beam of light streaming down onto his left shoulder. The beam whispers ‘chosen one.’ Another example is found in a popular marketing photo for the estate, now established as a private club and resort, Trump stands in a room covered almost entirely in gold leaf. For the portrait Trump chose an ensemble of golf attire, supported by a prop in the form of a golf club.The photo is shot fromjust above the ground as to give the proprietor a looming quality. He is surrounded by dark wood tables with gold trim and a pearlescent and ornately patterned living room set. In the center of the image, and just over his right shoulder, hangs a massive and elaborate chandelier. Each element of the room suggests pomp and splendor.

The historical object as wealth fantasy theme is sustained throughout estate, and even embedded in its construction. Privacy structures surround portions of the lawn, to sensor views of the surrounding developments. The walls are covered in what are referred to in a historical architectural survey and articles published in the first half of the century as Doria stone imported from Genoa.3 Doria is not actually a type of stone, but the name of a 12th to 16th century Genoese noble family. This would suggest that the stones were removed from the property of a Dorian estate, imported to south Florida, plastered to a new privacy wall, and displayed without any didactic information. The probable palatial stone is used throughout the estate, appearing in sculptures, fountains, and floor tiles, dusting the site with barely royal ruins.

![]()

The estate’s name translates from Spanish to English as Sea-to-Lake, as in the land from sea to lake, or better put, views from sea to lake, the sea being the Atlantic Ocean, and the lake being Lake Worth Lagoon. In a sense, this location is the mountain peak of the low-land swamp region, or, in other words, privileged land. All points are visible. Vistas from lake to sea, or, rather lagoon to ocean. The natural landscape, already a commodity, is further commodified, as it is packaged to provide a simulation of a slightly different landscape. Much of the landscaping is designed to protect the fantasy, or illusion, that the estate has cultivated. The oceanside boulevard was depressed to not obstruct the view of the ocean. This protects the inhabitants from the visual knowledge of the surrounding civilization. The privacy walls protect the property views where alteration to the outside world was not possible.

The continuity of the unobstructed view and dazzling privacy wall maintain the mystification of the visitor’s experience. Any location on the estate lawn posits the landscape as a staged scene, establishing a front and back side. The visitor becomes a member of the audience and the reality of a landscape that you can touch is confused with the fantasy of a play staged on a remote island. The creation and differentiation of front and back further fragments the visitor’s sense of reality. While writing on staged authenticity in The Tourist, Dean MacCannell describes the process of alienation that occurs in the front/ back separation, “The problem here is clearly one of the emergent aspects of life in modern society… a weakened sense of reality, appears within the differentiation of society into front and back. Once this division is established, there can be no return to a state of nature. Authenticity itself moves to inhabit mystification.”4 For MacCannell, this problem progressed to include a range of confusing tourist activities, like factory tours and the neo-liberal desire for an “authentic” experience of foreign places. The crisis of alienation that occurs while reading the Mar-a-Lago landscape lies in the tension between the fact that the landscape is present and the realization that it is also represented.

Library of Congress, April 1967 Doria stone covered main entrance gate looking up palm- lined drive. Photos from historical survey, HABS FL-195.

The estate’s name translates from Spanish to English as Sea-to-Lake, as in the land from sea to lake, or better put, views from sea to lake, the sea being the Atlantic Ocean, and the lake being Lake Worth Lagoon. In a sense, this location is the mountain peak of the low-land swamp region, or, in other words, privileged land. All points are visible. Vistas from lake to sea, or, rather lagoon to ocean. The natural landscape, already a commodity, is further commodified, as it is packaged to provide a simulation of a slightly different landscape. Much of the landscaping is designed to protect the fantasy, or illusion, that the estate has cultivated. The oceanside boulevard was depressed to not obstruct the view of the ocean. This protects the inhabitants from the visual knowledge of the surrounding civilization. The privacy walls protect the property views where alteration to the outside world was not possible.

The continuity of the unobstructed view and dazzling privacy wall maintain the mystification of the visitor’s experience. Any location on the estate lawn posits the landscape as a staged scene, establishing a front and back side. The visitor becomes a member of the audience and the reality of a landscape that you can touch is confused with the fantasy of a play staged on a remote island. The creation and differentiation of front and back further fragments the visitor’s sense of reality. While writing on staged authenticity in The Tourist, Dean MacCannell describes the process of alienation that occurs in the front/ back separation, “The problem here is clearly one of the emergent aspects of life in modern society… a weakened sense of reality, appears within the differentiation of society into front and back. Once this division is established, there can be no return to a state of nature. Authenticity itself moves to inhabit mystification.”4 For MacCannell, this problem progressed to include a range of confusing tourist activities, like factory tours and the neo-liberal desire for an “authentic” experience of foreign places. The crisis of alienation that occurs while reading the Mar-a-Lago landscape lies in the tension between the fact that the landscape is present and the realization that it is also represented.

The thematic design of the estate was fitting for the region and era. South Florida was marketed as a new tropical frontier, waiting to be developed as a land of second homes. In the early twentieth century the fantasy of south Florida as a winter playground for the wealthy was established and set in motion a permanent shift. The construction of tropical resorts in the region, like the Royal Poinciana Hotel in the late 19th century and the Biltmore Hotel in the early twentieth century, created an image of the region as a site of temperate leisure for the affluent that was advertised throughout the country. These images inspired the housing boom of the 1920s and successive housing developments at various scales for various incomes, but all for the middle class or wealthier. The short duration of the inhabitant’s length of stay, and the nature of being a second home, guided or loosened the direction of the regional design. In an article for the American Architect journal, Irvin L. Scott cites Mar-a-Lago in these terms, “The Palm Beach Estate of E. F. Hutton [husband of Merriweather Post at the time of construction] is intended as a place of comparatively short residence. Its situation is in one of our principal winter playgrounds where each day is a holiday and where people go to enjoy a semi-tropical climate for perhaps two months in a year. These factors seemed a rational argument for designing a house tending toward a richness, a festive quality, and one that could be well out of the ordinary.”5 As their second homes, these dwellings were touristic. The home itself is a fantasy place.

Library of Congress, April 1967 Entrance to owner’s suite from cloister.

Photos from historical survey, HABS FL-195.

Photos from historical survey, HABS FL-195.

Donald Trump and Melania Trump pose for a photo, 2011.

Photo by Damon Higgins / The Palm Beach Post.

Photo by Damon Higgins / The Palm Beach Post.

Physically, not much about the fantasy has changed through the transition of ownership. Symbolically, the site is reformed to represent the new form of the leisure class, reorganizing its content to add new meaning and recontextualize its new host. In ushering in the new, the past is rewritten to accommodate the future, just as the leisure class is reframed to valorize the producer of capital, the worker-president-host. A simple photo of the President golfing on the grounds alters the meaning of the site completely. It reflexively acknowledges itself as a living advertisement to the aesthetic of capitalism. While the new host is an extension of the old host, the profound difference between the two is the shift from the philanthropic façade as symbol for grandeur, and the leisure-worker as symbol of capital. Ultimately, both are made of the same ingredients: luxury, leisure, and power.

Supporters take photos in front of a portrait of Donald Trump

at Mar-a-Lago Tuesday Nov. 8, 2016. Aleese Kopf / Daily News.

Mar-a-Lago’s host is now the commodity. He is the image of the act of production, and a product in itself; the hybrid of the leisure class, the work, and the worker. The ideal to emulate is no longer an advertisement of the elite class that production creates, the leisure class, but is now an advertisement of the elite worker. Pre-presidency of the Trump era Mar-a-Lago, the estate was a museum to a cultural product/worker, i.e. the reality TV star and the high rise erector. Post-presidency, the resort becomes a museum to the top of the hierarchy of the elite worker: the president. Here you experience the same view as the president; you eat the same breakfast; you play the same 9-holes. The success of the host and resort can be credited to what MacCannell regards the act of modernity, “breaking up the ‘leisure class,’ capturing fragments and distributing them to everyone.”6 In this act, what is divided up for everyone is not the wealth, but the spectacle, and Mar-a-Lago visitors can buy a piece of that experience, one round of golf at a time.

Notes:

1 Yourish, Karen, and Troy Griggs. "Tracking the President's Visits to Trump Properties." The New York Times, April 23, 2018. Accessed May 25, 2018.

2 Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator, Marjorie Merriweather Post, Marion Sims Wyeth, Joseph Urban, Franz Barwig, Lewis & Valentine, and Cooper C Lightbrown. Mar-a-Lag, South Ocean Boulevard, Palm Beach, Palm Beach County, FL. Florida Palm Beach County, 1933. Documentation Compiled After. Photograph.

https://www.loc.gov/item/fl0181/.

3 ibid.

4 MacCannell, Dean. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013, 93. MacCannell writes on the sociologic rituals of tourism and the search for modernity. Applying Marxist theories in relation to things onto the economy of experience and cultural production, MacCannell locates modernity in the formation of ideologies constructed within sightseeing.

5 Scott, Irvin L. “Mar-a-Lago ‘Estate of Edward F. Hutton, Palm Beach, Fla.” The American Architect, v. 133 (June 20, 1928), 795-811.

6 MacCannell, 37.

1 Yourish, Karen, and Troy Griggs. "Tracking the President's Visits to Trump Properties." The New York Times, April 23, 2018. Accessed May 25, 2018.

2 Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator, Marjorie Merriweather Post, Marion Sims Wyeth, Joseph Urban, Franz Barwig, Lewis & Valentine, and Cooper C Lightbrown. Mar-a-Lag, South Ocean Boulevard, Palm Beach, Palm Beach County, FL. Florida Palm Beach County, 1933. Documentation Compiled After. Photograph.

https://www.loc.gov/item/fl0181/.

3 ibid.

4 MacCannell, Dean. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013, 93. MacCannell writes on the sociologic rituals of tourism and the search for modernity. Applying Marxist theories in relation to things onto the economy of experience and cultural production, MacCannell locates modernity in the formation of ideologies constructed within sightseeing.

5 Scott, Irvin L. “Mar-a-Lago ‘Estate of Edward F. Hutton, Palm Beach, Fla.” The American Architect, v. 133 (June 20, 1928), 795-811.

6 MacCannell, 37.